- Home

- /

- Features/Spotlight

- /

- Female gentile...

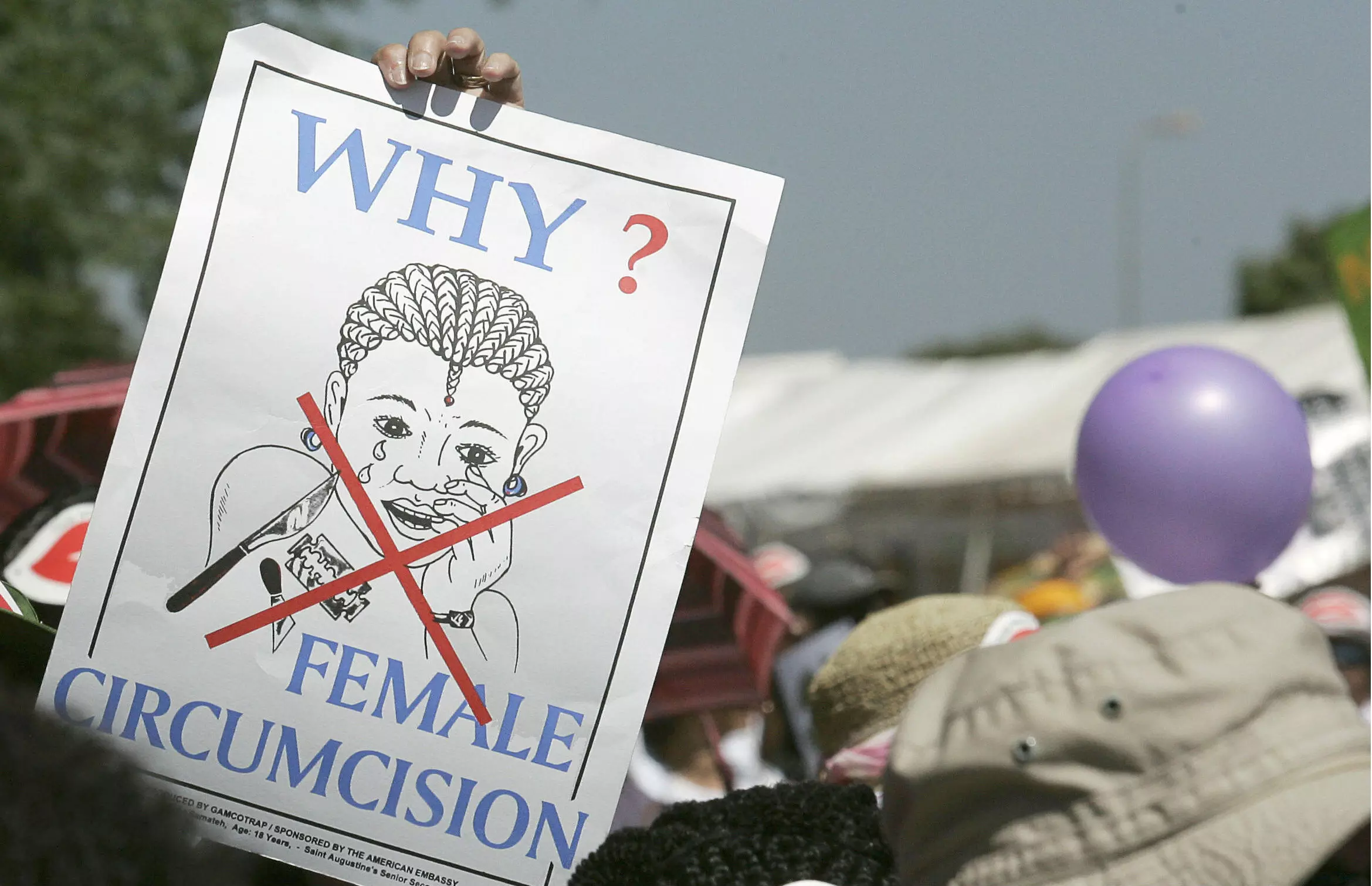

Female gentile mutilation a crime that must end

According to UNICEF, female genital mutilation (FGM) refers to all procedures involving partial or total removal of the female external genitalia or other injury to the female genital organs for non-medical reasons.

Over the years, it has been practiced in many Nigerian communities, especially in the South East, South-South, and South West.

Critics of the practice say that it is embedded in ignorance and misrepresentation of culture.

Ms. Karima Bungudu, Gender/FGM Analyst, UN Population Fund (UNFPA), says the practice constitutes a human rights violation.

She described it as the height of gender inequality occasioned by conspicuous discrimination against the female gender.

The UNFPA FGM Analyst wondered why women could be singled out for such a harmful practice, thereby stifling their potential to live life to the fullest.

“FGM is an infringement on the girl’s right to health; hence, its health complications can retard the girl's vision and dreams for a greater future.

“It is a violation of the girl’s or woman’s human rights to choices and self-preservation,” she said at a training for media professionals on FGM.

Bungudu said it was unfortunate that `the cruel practice of social, cultural, and gender inequitable norms and belief`, had been normalized.

She said the risk and complications increase with the type of FGM and may likely be more severe and prevalent with infibulations.

Experts say infibulation involves the narrowing of the vaginal opening through the creation of a covering seal.

According to them, the seal is formed by cutting and repositioning the labia minora or labia majora, sometimes through stitching.

Bungudu said: “Type 1: Also known as clitoridectomy, it consists of partial or total removal of the external part of the clitoris and/or its prepuce (clitoral hood).

“Type 2: Also known as excision, the external parts of the clitoris and labia minora are partially or totally removed, with or without excision of the labia majora.

“Type 3: It is also known as infibulation or pharaonic type. The procedure consists of narrowing the vaginal orifice and creating a covering seal by cutting the labia minora and/or labia majora, with or without removal of the external part of the clitoris.

“The appositioning of the wound edges consists of stitching or holding the cut areas together for a certain period of time (for example, girls’ legs are bound together) to create the covering seal.

“A small opening is left for urine and menstrual blood to escape.

“Type 4: This type consists of all other procedures to the genitalia of women for non-medical purposes, such as pricking, piercing, incising, scraping, and cauterization,” she said.

Gender advocates say the practice has remained because those who carry it out have not been penalized by the authorities and call for the implementation of relevant laws to end the practice.

A UNFPA report says that about 14.8 million girls and women are at risk of being cut in the future, with 19.9 million girls in Nigeria having gone through the practice already.

It is estimated that some 200 million girls and women globally have undergone some form of female genital mutilation.

UNFPA estimates that globally, 68 million girls are at risk of being mutilated between 2015 and 2030.

Dr. Aliyu Yakubu, Ag. Head, UNFPA Cross Rivers, told the News Agency of Nigeria (NAN) that FGM had destroyed not just the lives of women and girls but also those of newborns.

Yakubu said FGM poses a lot of health hazards for women and girls, both during birth and after.

He said that it could lead to fatalities during birth as a result of the tightness of the birth canal, which could have been stitched during FGM.

“During birth, the scar tissue might tear, or the opening needs to be cut to allow the baby to come out”, he said.

Mrs. Aduke Obelawo, an anti-FGM advocate, said that the practice is a crime against humanity, especially women and girls.

“After childbirth, women from some ethnic communities are often sown up again to make them “tight” for their husbands.

“Such cutting and stitching of a woman’s genitalia results in painful scar tissue”, she said.

Dr. Juliet Ofo of the Federal Medical Centre (FMC) Jabi said that FGM could result in death through severe bleeding and neurogenic shock as a result of pain and trauma.

Ofo said the harmful practice has the propensity to trigger overwhelming infections and septicemia.

Ms. Ayo Bello, Head, Global Media Campaign to End FGM, told NAN there was a need for synergy among media professionals to amplify the advocacy to end FGM.

Bello tasked the media with educating the public about the need to end FGM by exposing its hazards and consequences.

Bello expressed hope in the power of the media to end FGM by holding governments accountable.

She called for social activism using the media as a platform to change the narrative of the normalization of FGM.

Mr. Franklin Ihemefor of the African Episcopal Methodist Zion Church (AEMZC) affirmed the position of some clerics that FGM had no link to Christian religion.

Ihemefor said that it instead reinforces obnoxious cultural practices targeted at women and girls.

Dr. Zubaida Abubakar, Gender/GBV Specialist, UNFPA, also said that the pain inflicted by FGM often continues as ongoing torture throughout a woman’s life.

Abubakar said that with the cutting, women experience various long-term effects, such as physical, sexual, and psychological.

She called for coordinated and systematic efforts to end female genital mutilation, engaging whole communities, and focusing on human rights and gender equality.

Abubakar, who said the procedure is most often carried out on young girls between infancy and age 15, added that it is a violation of girls’ and women’s fundamental human rights.

As society battles FGM, overcoming the challenges depends largely on smooth partnerships among stakeholders, including religious groups such as development partners, health workers, civil society, and the media.

By Ikenna Osuoha